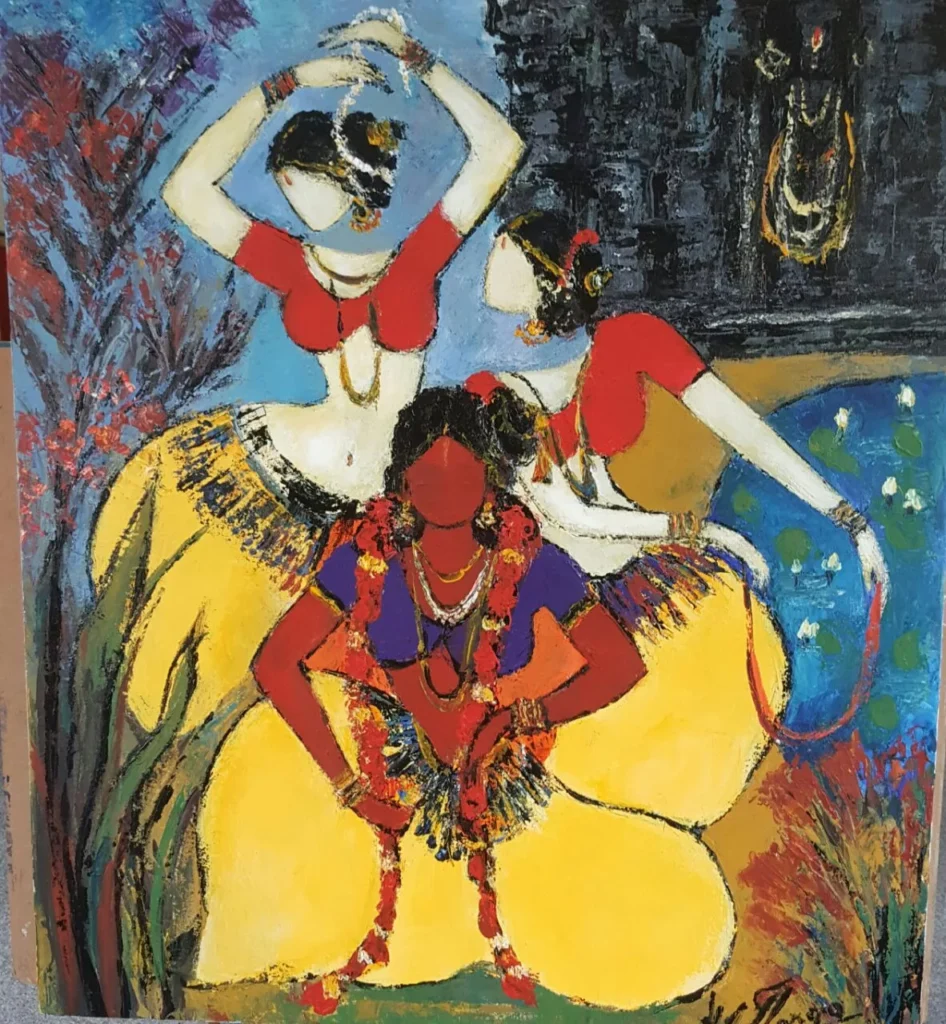

Among many pursuits of mine, ‘What is true beauty?’ was a pertinent question for me to be a complete artist. It is when destiny led me to visual artist Sri A. V. Ilango, he opened new doors and windows which showed me a less explored path. Being his muse is a privilege that added meaning to my years of rigour in dance; for, he has made my tryst with Mohiniyattam timeless.

To share my experiences with him- from the beginning, he never separated me from him, and he used to share with me accounts of his journey in art, of his lines, the who and what influenced it. I could quickly grasp that in capturing ‘me’, he was not capturing my physicality, but the essence of who I am. So in the initial stages when he captured me while dancing, he was capturing the energy lines of Mohiniyattam or the sentiment I was portraying. This part of what he was doing I could relate perfectly. However, when he used me as an object to teach his students on Space and Form: in stillness and movement, his comments would become suddenly cryptic. In all fairness, he was explaining well even at that time, only we (his students and I) lacked the knowledge to grasp what he was saying. For eg., he would say, ‘Capture her tendency, and let art happen’. ‘Tendency?!… What the hell is this tendency?’, we would all be murmuring inside our heads, letting thoughts wander.

It was not until I learnt the yogic anatomy and the composition of the body and mind, that the matrix hidden in his comments revealed to me. I may struggle in articulating what got revealed, but here is an attempt.

Indic knowledge systems explain ‘form’ not as the gross potential of an object, but the subtle potential within it that is subject to change, but remaining hidden to plain sight. And since visual art is a form that unveils the unseen, this hidden potential is what a traditional artist is constantly trying to bring forth through forms.

So, Ilango’s engagement with dancers and movements is an exercise of gaining control of the gross elements in himself, to scale it, and match it with the hidden potential of the dance. In his pursuit, his gift is his ability to see movements, and capture it as is. His lines are hence lyrical, subtle and forceful changing constantly to the dance inside of him, or that of the dancer who he engages him. This makes Ilango’s works true to the object, as he mutes the subject: his own self. This method is also the same as what Indian classical composers and traditional artists try: exploring laya (that which pulsates) or discovering patra (that which portrays). Every sculptor belonging to medieval India also used the visual process. Their search for ‘the ideal’ have led them to forms, which evokes or reveals every time on revisiting it. Therefore, medieval Indian art was housed in open for the public to engage in, which resulted in the construction of temples. Generations have passed, but still the art they left behind has continued to engage seekers and connoisseurs.

To experience Indian art forms in their glorious best, Jvala has chosen Chola’s capital city as the destination. At Thanjavur all types of traditional forms were nurtured in the temple – rituals, music, dance, sculpture and painting making the Chola art a living tradition.

PS: The visual artistic process is more spontaneous involving pure awareness and different to what most contemporary artists are schooled in institutions. Most contemporary artists express the object of art as the subject. Their engagement with the object may have revealed something to them, which they express as subject. In this method too the ideal is explored; but what has gotten revealed to the artist may not necessarily become a scope to grasp for the spectator who are viewing the art. Hence, this kind of art is exclusive only for the classes.